Viability of the Global Life Insurance Industry

IIS Executive Insights Life & Health Expert: Ronald Klein, Executive Director, BILTIR

Insurers Are Exiting the Individual Life Insurance Business

What is happening in the world of life insurance?

The Hartford discontinued sales of individual life insurance in 2012*. MetLife spun off its life insurance business into Brighthouse Financial in 2017. VOYA Financial exited the individual life insurance business in 2018. AXA sold its share in Equitable, its U.S.-based life insurance business, in 2019. AIG announced that it will split off its life and retirement business in 2020. Prudential plc, of the United Kingdom, announced the demerger of Jackson National Life, its U.S.-based life and retirement business. The American firm Prudential Financial announced that it will sell its retirement business and is considering further “de-risking,” including variable annuities and other products with guarantees. And these are just a few of the announced divestitures from the life insurance business by major insurers.[1]

Is the sale of individual life insurance coming to an end? Insurers are certainly still selling it, but in this lingering environment of ultra-low interest rates, pressure is mounting from shareholders to sell off all or certain blocks of life insurance. That is why one prominent insurer’s CEO said, “I think that life insurance is a mutual company product.”[2]

Not only are low interest rates making it difficult to earn a decent return on these products, but some insurers also have products on the books with minimum guarantees that they just cannot keep up with any longer. To add insult to injury, insurers must also hold regulatory capital against these policies and manage costly legacy administration systems. Announced changes to insurance regulations are tending toward increasing regulatory capital for long-dated guarantees, rather than decreasing it. Updating systems for old insurance policies does not seem like a good use of shareholder money.

Shareholders Demand Better Returns

Shareholders are becoming increasingly vocal about the returns on capital for life insurance. This is especially true for companies that must adhere to Solvency II regulations, which require insurers to hold excessive capital in support of long-term guarantees. A combination of low yields on assets and overbearing capital requirements makes life insurance increasingly difficult for stock insurers to maintain. One prominent board member of a life insurance company aggregator said the insurers that do not sell certain blocks of life insurance business “run the risk of activist investor action.”[3] While life insurance is generally thought of as a long-term business with many policies in force for decades, activist investors generally represent investors with much shorter time horizons. This mismatch of expectations can wreak havoc for life insurers and their policyholders.

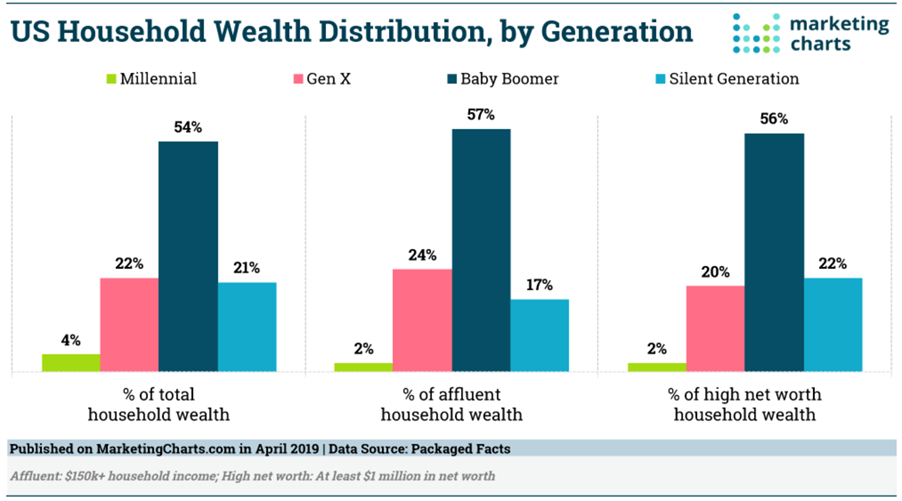

The life insurance industry has focused on baby boomers for decades, and for good reason. Baby boomers still hold over 50 percent of total household wealth compared with other generations (see Figure 1).[4] This large group of people born between 1946 and 1964 purchased pure protection products to pay off mortgages and college costs for their children in case of premature death. Then they purchased life insurance savings products as they advanced in age and became more affluent. Then they purchased annuities to protect against outliving their retirement assets.

However, this era is coming to an end, as the youngest baby boomers are now in their late 50s and most are well into their 60s and 70s. Life insurers now realize that they have to invest in new technologies to attract other demographic groups, such as millennials. Freeing up large amounts of capital backing life insurance products to invest in technology seems like a better use of this money—and it is what shareholders are demanding.

The life insurance business is still extremely important and will continue to be so. It protects breadwinners from the financial consequences of premature death, disability, or outliving their assets. According to the Financial Stability Board, insurer assets in 2019 amounted to $35.4 trillion (USD).[5] In 2016, the International Monetary Fund estimated that 85 percent of insurance assets can be attributed to life.[6] That means that the life insurance industry is responsible for approximately 7.5 percent of the $404.1 trillion (USD) of financial assets worldwide. Not too bad for an industry that seems to be selling off its businesses.

Not only does the industry invest these assets into corporate bonds, infrastructure, and government bonds, but benefit payments in the U.S. alone amounted to over $530 billion.[7] The life insurance industry continues to be a noble undertaking.

Divestiture Strategies Vary

Insurers can use several different methods to off-load blocks of life insurance business. They can stop writing new policies and manage the old policies as a run-off business. They can reinsure the old policies but continue to service and administer the policies. They can spin the business off into a separate company. They can reinsure the business and transfer the servicing and administration. Or they can sell the business to another organization, most likely to an aggregator. Each technique has its benefits and drawbacks, and hybrids may also be used. This paper will focus on the aggregation model, which has become more prominent during the past few years.

Through economies of scale, aggregators service and administer policies and may be able to invest a bit more efficiently than the seller was. Recently, the aggregator business has become quite competitive, with many new entrants, especially in the U.S. market. Aggregators can also domicile in jurisdictions with the most favorable capital requirements for their specific business models, thus reducing regulatory capital and increasing returns to shareholders.

The economics for this type of business seem to be working for both buyers and sellers, but what about the policyholder? This is exactly what insurance regulators around the world are exploring. With the increase in activity, regulators are “looking into the financial, operational and investment risks associated” with these transactions, according to recent conversations with four regulators.[8] They are also concerned with policyholder protection. However, the chair of the board of a major aggregator recently said that regulation is “driving this business, not impeding it.”[2] The president of another aggregator said that as long as there is “sufficient capital to back the policies, regulators are happy.”[9]

But there is more to in-force life insurance than simply paying benefits. Policies need to be updated as family circumstances change. If an aggregator is running off a block of business, the policyholders may not be receiving important services they need to keep their policies up to date with changing needs. Aggregators will say that they actually do a better job servicing the policies since run-off is their core business. The systems are newer and designed specifically for this business model, and the aggregators do not have new sales to offset lapses. Therefore, they need to maintain or improve persistency in order to meet shareholders’ expected returns.

Since most aggregators do not offer new policies, many policyholders may not be offered updates in coverage to meet changing needs in their lifecycles. The selling company will say that its agents and brokers will continue to treat these policyholders as customers, but regulators are becoming wary. One prominent European regulator said that he would not approve the sale of a block of life insurance business when a third-party services the policies.[10] This regulator believes that the biometric and policyholder-behavior risks need to be with the same company as the administration. This, however, is not the norm in the U.S. or even other parts of Europe.

Another issue raised by regulators is the large—and growing—life insurance protection gap. Swiss Re estimates that the global mortality gap has reached $408 billion in 2020, a 6 percent increase from 2019.[11] It seems unfathomable that the protection gap increased during a pandemic, when people were focused on their own mortality and that of family members. Others will argue that the pandemic impeded agents’ ability to sell policies by making it difficult to schedule paramedical exams and keeping people out of the office.

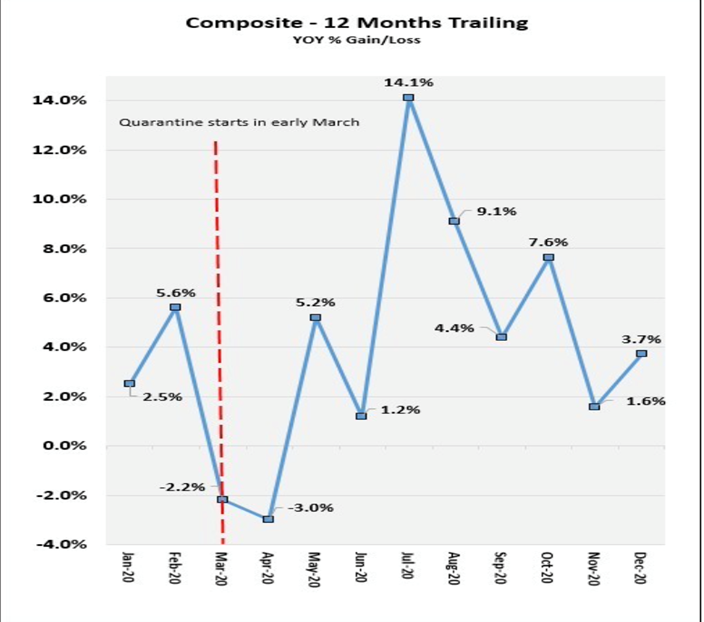

However, many insurers increased non-medical underwriting limits, making it easier to purchase life insurance without any additional exams. The Life Insurance Marketing and Research Association (LIMRA) announced that while new life insurance policy sales in the U.S. increased by 2 percent in 2020, annualized premiums dropped by 3 percent.[12] People were definitely considering purchasing life insurance during the pandemic, as the Medical Information Bureau (MIB) showed an increase in applications during 2020 (see Figure 2) but did not complete the purchase.[13] Some refer to this as the intention gap, another disturbing trend that needs to be addressed. Flat life insurance sales during the worst pandemic in 100 years is disappointing, nonetheless.

Source: Medical Information Bureau

Technology Can Help

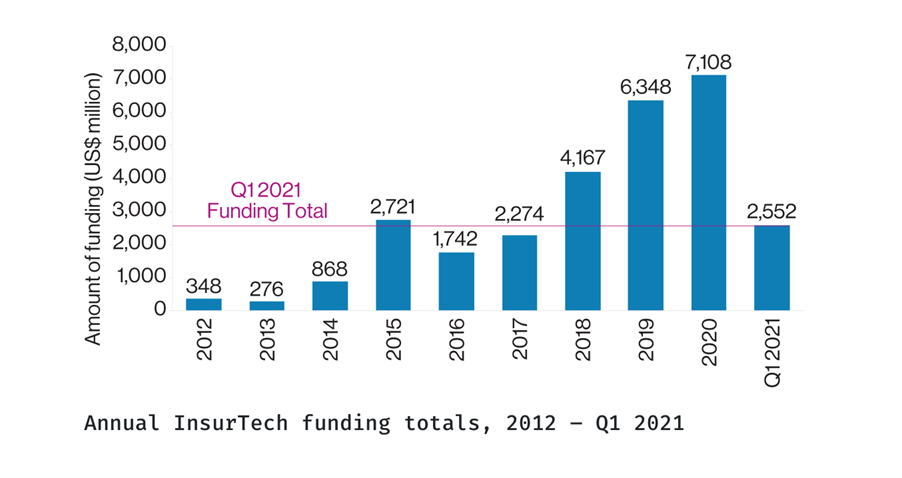

There has been a lot of talk in the industry about technology. Life insurers are investing millions of dollars and dedicating much time in start-up companies that claim to issue policies in minutes and to have developed more efficient underwriting and better fraud management. Willis Towers Watson (WTW), in its “Quarterly InsurTech Briefing Q1 2021,” announced that investment in insurtech for Q1 2021 reached an all-time high of USD 2.55 billion, spread over 146 deals (see Figure 3).[14] About 31 percent of this funding is associated with the life insurance industry. WTW says that it will soon have to drop the term “insurtech” as these new technologies are becoming the norm. Even with the multitude of start-ups and insurtech investments, worldwide life insurance sales have been flat at best. Will these new ideas eventually gain traction that turn into tangible insurance sales?

Source: Willis Tower Watson, “Quarterly Insurtech Briefing Q1 2021”

One area of increased interest is in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). However, this technology is not as advanced as people might believe. Try asking an automated assistant to dial the phone of a friend with a foreign name. Sometimes, no matter how many times you say the name, the assistant just cannot understand it—until you receive a response such as “Ordering pizza.” (Although nice, hot pizza may take your mind off of whomever you were trying to call.)

In the insurance industry, AI has mainly been used for non-life insurance—particularly in fraud detection. With vast amounts of data now available, machines can comb through seemingly endless numbers of claims to search for patterns in suspicious claims submissions. Machines can find certain repetitive behaviors not easily discovered by humans. Not only can claims managers use AI to assist in identifying potential fraud, AI can also help find ways to prevent fraud.

AI is also being used more and more in the field of auto insurance, especially with telematics and autonomous vehicles. A newer use of AI is to match up a caller with the correct servicer. Using data such as previous issues, age, location, and policy type, machines can learn how to increase sales and decrease lapses. Call-center activity is vitally important to the success of auto insurers, yet this activity is typically delegated to operations or IT. Perhaps it is time to realize that call centers should be under the control of the sales team.

For life insurance, the only real use of AI has been in the field of medical underwriting. Risk assessment is probably the most important aspect of life insurance, and companies spend a lot of money choosing their risks carefully. This typically involves costly paramedical exams, blood tests, nonmedical questionnaires, and perhaps stress tests. These tests are not only expensive, they are time-consuming and can severely delay the delivery of a policy. Agents complain that lengthy delays in policy issuance are a major cause of non-taken ratios—which could increase the intention gap, discussed before. Using AI to select risks more quickly and without time-consuming and expensive exams could lower prices and speed delivery of policies. This can help close the intention gap and increase sales.

Another use of AI for life insurance could be in the field of in-force management. Given the robust market for blocks of in-force life insurance business and the continuing need for protection, it may be time for a change to the current business model. Imagine using AI to examine in-force policyholders and determine which were in need of policy changes—increase in face amount, sale of new products (annuities, long-term care, disability, etc.), decrease in face amount (could prevent an imminent lapse and help build customer loyalty). Using AI as a tool to assist agents in identifying customer needs could be very powerful.

Aggregators could use AI to sift through in-force life insurance policies to determine which are best suited for policy changes. If the aggregator does not issue new policies, it can contract with third-party insurers to write the new policies and receive a commission. This would be good for all parties. The aggregator makes extra returns for its shareholders by marketing a highly valuable asset—its policyholders; insurers have a great source of new business—people who have already purchased life insurance and who have been identified by AI as likely to purchase additional insurance; AI companies can sell their software to aggregators and insurers; and, most importantly, policyholders are given the opportunity to purchase important products to help secure the financial well-being of their families.

Conclusion

Life insurance is a very involved business. Insurers must develop complex products that can last more than 50 years. Then they must market and sell these products using an array of channels. Applications must be underwritten carefully to mitigate the risk of anti-selection. Once a policy is sold, it must be administered, which includes allowing for a host of policy changes. Reserves and capital held against these policies must be invested prudently according to strict regulatory guidelines. Claims and other benefits must be paid with a watchful eye for fraud.

Traditionally, these completely different competencies have typically fallen under one roof. But there seems to be change in the wind. With a combination of a low-interest-rate environment, the Great Recession, a once-in-100-years pandemic, and stricter regulation, it is becoming more and more difficult to manage all aspects of life insurance while meeting shareholder expectations. The life insurance industry is decentralizing before our eyes. It is too early to say whether this new approach will be successful, but if interest rates remain at record lows, the odds of this happening increase.

Regulators will continue to scrutinize this evolving business model with the goal of protecting policyholders. The worst thing for a policyholder, insurer, and regulator is for a life insurer to be unable to make a claim payment, especially if the policyholder has been paying premiums for 30 or 40 years. One default could destroy the entire model.

The sale of individual life insurance may well be best suited to mutual companies, but the new model that is emerging might be well suited to insurers, aggregators, shareholders, regulators, and, most importantly, policyholders. Bringing the many activities that life insurers currently perform under one roof to separate companies that excel in one or two of these competencies may be the wave of the future. New technologies such as AI can assist in meeting policyholder needs. Regulators will have to show some flexibility and patience. It will be very interesting to see how the life insurance industry evolves.

Who said the life insurance industry is dull?

8.2021

About the Author:

Ronnie has over 40 years of insurance and reinsurance experience having worked and lived in 3 countries. In his current role, Ronnie serves as Executive Director to the Bermuda International Long-Term Insurers and Reinsurers (BILTIR) association. He also is a Collaborating Expert of Health and Ageing for The Geneva Association located in Zürich. Ronnie is Co-Chair of the Programming Committee for the ReFocus Conference and served on the Board of Directors of the Society of Actuaries. Before this, Ronnie worked as the Head of Life Reinsurance for Zurich Insurance Group in Zürich, Head of Life Reinsurance for AIG in New York and Global Head of Life Pricing for Swiss Re in London. Ronnie began his career at Mutual of New York. A little-known fact is that Ronnie holds a patent (US20060026092A1) for the first Mortality Bond issued called Vita when he was with Swiss Re.

*The Hartford continues to sell group life insurance

[1]Matthew Sturdevant, "The Hartford to Sell Life Insurance Unit to Prudential in $1.5 Billion Transaction," Hartford Courant, Sep. 27, 2012; Metlife, Inc., "MetLife Completes Spin-Off of Brighthouse Financial," Aug. 7, 2017; Leslie Scism, "Another Insurer to Cease Selling Life Insurance to Individuals," The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 30, 2018; AXA, "AXA S.A. announces the sale of its remaining stake in AXA Equitable Holdings, Inc.," Nov. 7, 2019; Suzanne Barlyn and Alwyn Scott, "AIG Names New CEO, Plans to Spin Off Life and Retirement Unit," Reuters, Oct. 26, 2020; RTTNews, "Prudential Plc Now Expects Jackson Demerger to Complete In H2'21," May 13, 2021; Prudential Financial, "Empower Retirement to Acquire Full-Service Retirement Business of Prudential Financial, Inc.," July 21, 2021.

[2]Personal conversation on June 17, 2021.

[3]Phone conversation on July 1, 2021.

[4]Marketing Charts, “Baby Boomers Possess the Majority of US Household Wealth,” April 8, 2019.

[5]Financial Stability Board, “Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation 2020,” December 16, 2020.

[6]International Monetary Fund, Global Financial Stability Report, p. 88, April 2016.

[7]American Council of Life Insurers, Life Insurers Fact Book 2020, p. xiv, 2020.

[8]Phone conversations on July 2 and July 13, 2021.

[9]Phone conversation on July 7, 2021.

[10]Phone conversation on July 2, 2021.

[11]Allison Bell, “Swiss Re Sees $408 Billion Mortality Protection Gap,” ThinkAdvisor, June 16, 2021.

[12]LIMRA, “U.S. Life Insurance Policy Sales Increase 2% in 2020,” March 18, 2021.

[13]Cision, “U.S. Life Insurance Activity Hits Record Growth in 2020 Reports the MIB Life Index,” January 13, 2021.

[14]Willis Towers Watson, “Quarterly InsurTech Briefing Q1 2021,” April 28, 2021.